The Holmul Archaeological Project first (since 2000), and now the Maya Archaeological Initiative (since 2010) help protect the Classic Maya city of Holmul employing four park rangers to guard the site 24/7. In addition to patrolling the site to prevent looting, the rangers take measures to protect the site’s structures from erosion while maintaining roofs, trails and research camp facilities in good usable conditions. In addition, Holmul rangers monitor and maintain the nearby minor sites of T’ot, Riverona, and K’o.

The ancient Maya city of Holmul (17 18′ 14.792″ N, 89 15′ 29.264 W) is located on an upland ridge where the Holmul River turns from an easterly course north towards the Bay of Chetumal. It was first settled around 1000 BC. During the Preclassic period it became and important ceremonial center in the vicinity of Cival, the major center in this region. In the Terminal Preclassic, as Cival experienced a decline, Holmul was still an important place for elite ceremonies and grew in importance becoming the capital of an important kingdom in the Classic period. Its Classic rulers were allied with Tikal at first, and with the distant Teotihuacan, from AD 378 until circa AD 500. It was ruled by vassals of the Naranjo kings in the Late and Terminal Classic. As many other ancient cities in the southern Lowlands, it entered a rapid decline around AD 830 and was largely abandoned by AD 900. Since then, the site and its sprawling residential areas have been reclaimed by a beautiful tropical hardwood forest peopled by monkeys, jaguars, deer,peccaries, tapirs and many other endangered species. The archaeologists’ camp is situated on the Holmul river 2 km from the main Holmul hill top plazas. It is furnished with sleeping huts, latrines showers and kitchen for park guards and guests. Visitors can set up their tents on the camp grounds. From Yaloch lake drive for 14km on a narrow logging road along the lake northern side (dry season only).

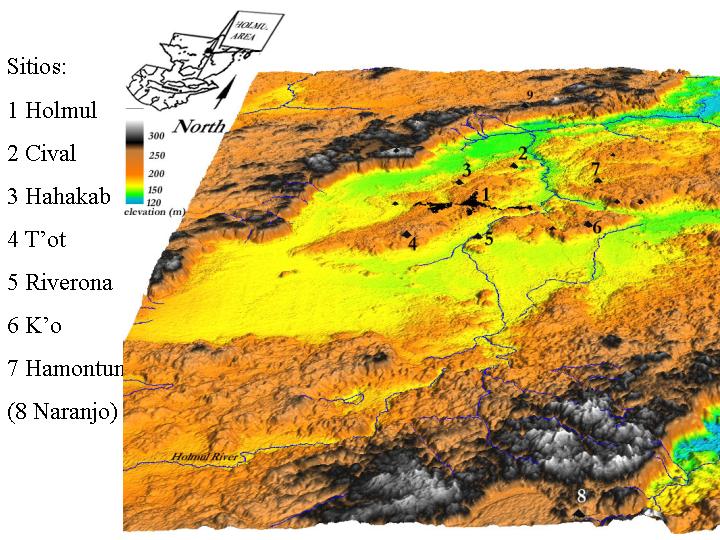

9 Witzna’ View of HOLMUL from Witzna’

Discovery

Holmul (Yucatec for “head of the mountain”) was first discovered by a 1909-1911 Peabody Museum of Harvard University expedition led by Raymond E. Merwin. Merwin and his mentor, Alfred Tozzer, learned about the site from the Count De Perigny who presumably had heard about it from local people a few years before. This expedition was important in many respects for Maya archaeology and for the future of the site. Merwin’s work set the standard for correlating Maya architecture, burial and ceramics in a chronological framework for all future archaeologists. He established a first ceramic stylistic sequence and uncovered many elegantly furnished tombs that are among the earliest in the Maya Lowlands, dating to AD 150. The tomb ceramics were among the most beautiful the Maya ever produced and have been often included in museum exhibits around the world (see recent exhibit, Fiery pool of the Maya). Today, they are permanently housed in the Peabody Museum at Harvard. At Holmul, Merwin documented exquisite palaces and temple buildings in very good conditions of preservation. Since these early findings, the ancient ruin has been fairly well know and referred to by many scholars. However, because of its remote location and because no carved inscriptions were found, the site was neglected by everyone else but looters since then.

Looting at Holmul

In 1974, the Guatemalan government placed guards on the site in response to a wave of massive looting throughout the Peten. Unfortunately, the measure came in late as many important buildings had been already damaged by illegal tunnels and trenches, some quite severely. In 1996, because of budget cuts the Guatemalan government was forced to remove the site guards. Looters returned to the site and inflicted additional damage to most buildings at the site. In 2000 guards were reinstated by the Holmul Archaeological Project, led by Francisco Estrada-Belli, who began a long-term archaeological investigation in the region that same year. In spite of the looting, the site still has preserved much of its original architectural beauty and all of its splendid wilderness.

Maya Architecture at Holmul

There are three major architectural complexes at Holmul. Group I, is the largest and tallest. It sits on a 20 m high platforms accessed by monumental stairways from the south (from the Main Plaza), and from the east and west sides. Its broad summits supports what sometimes is referred to as an acropolis in Maya archaeology. That is a group of masonry buildings around a courtyard. A long multi-roomed building (Buildings A and B) runs along the south side and has three monumental doorways opened to the plaza below. Its central room had doorways to the back as well, and was probably the main access to the courtyard. The courtyard was almost completely occupied by a 13 m high pyramid (Building D, of Group 1) which presumably supported a temple or palace, now largely destroyed by erosion and looting. On either site of this pyramid were palace-like residential units. The one to the west, was the main one. It boasted a finely stuccoed throne bench that was likely the seat of Holmul’s last ruler. Building F, located on the east side of the courtyard was a funerary structure dedicated to one of Holmul’s late rulers. Among his ceramic offerings were a Holmul Dancer-style cylinder and a tripod place. The latter had a lengthy inscription which attributed the plate to a Naranjo king, Bat Kawiil, who presumably donated it to the nameless Holmul ruler sometime during his short reign around AD 780.

The Group III is palace complex on a much shorter platform (4m high) that is split into two courtyards (Courts A and B) connected at a corner. It occupies the south side of the Main Plaza, across from Group I. With Ruin X, a stand-alone pyramid measuring some 12.5 m in height it defines the Main Plaza as the most important space for royal rituals. Court A is the southernmost. It measures 31×37 m. It is framed on all sides by multi-room buildings with doorways onto the plaza as well.

Its interior is mostly taken up by Structure 2 a 12m pyramid with a single-room building atop. Unfortunately, the pyramid has been completely bisected by looters trenches with side-to-side tunnels on three levels. Its core is made of five construction phases.

Court B, the northernmost, has a monumental stairway on the south side, leading up to a room with an arched doorway onto the courtyard. At the opposite side of the courtyard is Structure 43, a large rectangular building with large thrones in the center, north and south rooms. On either side of this structure as well as out in the back, were smaller and more private courtyards surrounded by narrow multi-room buildings. These were in all likelihood the residences of Holmul’s rulers family and courtiers. A narrow vaulted passage way still leads from the main court space to a more secluded courtyard behind Structure 43. This was the only passageway and it underscores the private nature of the northern part of Court B.

Court B was occupied by Holmul’s rulers probably from AD 600 to 744, after which time, the ruling family likely moved to the higher and more private residences on top of Group I described earlier.

Group II is located 200 m northwest of Group I. It can be accessed from Group I through a broad causeway (Merwin Causeway) leading to the ball-court before reading Group II. The complex is built atop a 4 m high platform with all major buildings facing south. The largest is Building A, which occupies the southeast portion of the group. It differs from most other Maya buildings from having a narrow doorway offset onto the west side. There is a veneer sculpture mask on the east and southeast sides of the building which resemble Terminal Classic veneer sculptures elsewhere in the Lowlands and especially in Yucatan at that time. The doorway was also originally surmounted by a masonry mask sculpture as many northern buildings were. Its interior, present an odd layout. It is largely composed of fill, except for a narrow L-shaped hallway leading into a tomb. The tomb interior is occupied by much rubble from the collapsed vault and was reportedly in the same condition at the time of Merwin’s expedition. No mention was made of any findings in this building.

Two pyramid mounds stand behind (north of) Building A. Building F and Building B. The latter was excavated by Merwin. He removed the topmost bulk of the last construction episode to reveal a well preserved, stuccoed multi-room building of Late Preclassic date. Within its three main rooms, he found the buried bodies of 18 individuals. The offerings accompanying these interments date the closing of the rooms to the period between AD 350 and 450.

Below these rooms were tombs dating to the Terminal Preclassic period, AD 75-250, whose polychrome ceramics are among the earliest in the Lowlands and have been the subject of much debate among scholars as to their function ever since 1911.

Below these levels, the Holmul Archaeological Project located three additional phases of construction, the earliest of which is dated by C-14 to 350 BC. This earliest among Maya temple buildings, was decorated with monumental sculptures depicting monstrous zoomorphic deities on its façade.

Buildings C and D stood to the west of Building A atop the Group II platform and were only partially excavated by Merwin. He documented their residential nature with associated burials.

In 2007, the Holmul Archaeological Project located a new temple edifice, Building N, in the levels below the upper Group II floor in the space between Building B and C, in the northwestern corner of the group. This finely stuccoed three-terraced pyramid had been completely buried by rubble during a renovation and rearrangement of the Group II space at the end of the Preclassic period. Building N was the last of three phases of construction whose beginning go back to 350 BC (and is coeval with Building B). Its main feature was a large zoomorphic sculpture in stone and stucco on the center of its upper terrace. This sculpture was largely destroyed during the renovations, which removed its upper half. What remains, is the lower jaw of a crocodilian-like creature.

Building N being unearthed under the floor of Group II

In 2009, during investigations of the lower level of Group II, a new early temple was discovered under Building F. This was a fully preserved twin-room masonry building atop a three-terraced pyramid, much alike Building B. Its construction dated also to around 350 BC. While no masks were found to decorate its façade (to the south), traces of red paint were found on the temple’s outer walls.

These latest findings reveal a monumental setting atop the Group II platform, dating to 350 BC. Three south-facing temples lined up on the northern edge of the platform. The central one, Building B, was the focus of the complex and was more elaborately decorated with sculptures identifying the deities it was dedicated to. These temples defined the northern (most sacred) direction of an open ceremonial space atop Group II. Moreover, the southern part of this space was possibly occupied by additional temples still lying undetected under Building A. Using Group II as a guide, it is likely that substantial Preclassic architecture, still undetected, may lie within the 20m high bulk of the Group I platform.