Cival is an ancient Maya city in northeastern Peten, located 7 km north of the ancient city of Holmul. It owes its name to a sinkhole near its main hill. It was first visited in 1911 by Raymond E. Merwin. During his explorations of Holmul for the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, Merwin photographed an early carved stela labeling it ‘Cival’ which later could not be located by British explorer Ian Graham, who returned to the site on behalf of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Harvard University in the 1980s. On that occasion, Graham mapped the main plaza and the site’s largest buildings. He noted its approximate locationon a mule-train road between Holmul and the Paso Benchuga logging camp, 55 km north of the present day town of Melchor. Following on Ian Graham’s recommendation, in the summer of 2001, Guatemalan archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli re-discovered the site, in spite of the mule-train no longer existing by spotting it on a LANDSAT satellite image. That same year, during the explorations Estrada-Belli’s Holmul Archaeological Project[i] a stela was found partly hidden by a large looters’s trench in the main plaza’s eastern building. Later Nikolai Grube, with the assistance of explorer Marco Gross, recorded the monument and identified it as the missing stela from Merwin’s photo, i.e. Cival Stela 2 (see below; a fragment of another monument, Stela 1, was also found nearby).

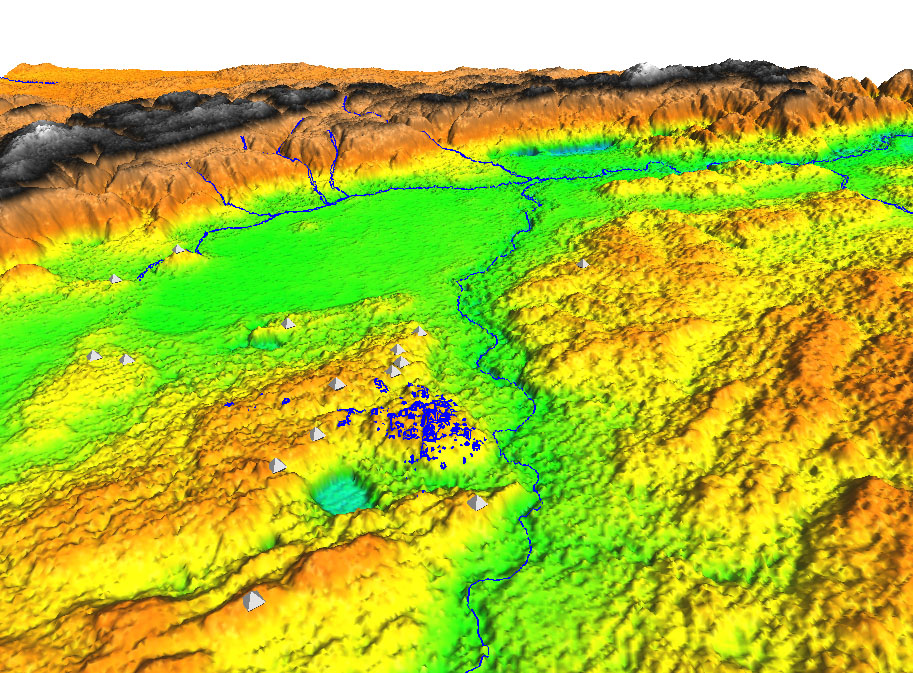

map of Preclassic sites Topography of Cival derived from AIRSAR data (courtesy of NASA). View towards Cival from Holmul pyramid

The site has been under investigation and the care of the Holmul Archaeological Project since 2001. Today it can be accessed by taking a difficult logging trail off the main gravel road that heads north from Melchor de Mencos through the Maya Biosphere Reserve along the Belize-Guatemala border. The road reaches the beautiful lake of Yaloch (where there is a military post). A trail heads northwest from there through the logging camp of Limon. A good 4×4 truck with mud tires and an expert guide are recommended for the trip. Four park rangers live at the Cival camp year round and can lead visitors through the site’s many trails and plazas. The camp is situated on a large aguada of the Holmul River which provides plentiful drinking water year-round. It is equipped with a kitchen/mass hut, outhouses and an additional thatched house for visitors to hang their hammocks.

Cival’s history

Cival distinguishes itself from most other Maya cities for having been occupied exclusively during the Preclassic period or between 900 BC to AD 200. Traces of earlier occupation were found in nearby lake deposits dating as far back to 1300 BC. These are in the form of maize pollen and other signs of human-alterations of the natural forest (burning and deforestation). Deeper untested deposits may contain evidence of even earlier human occupation.

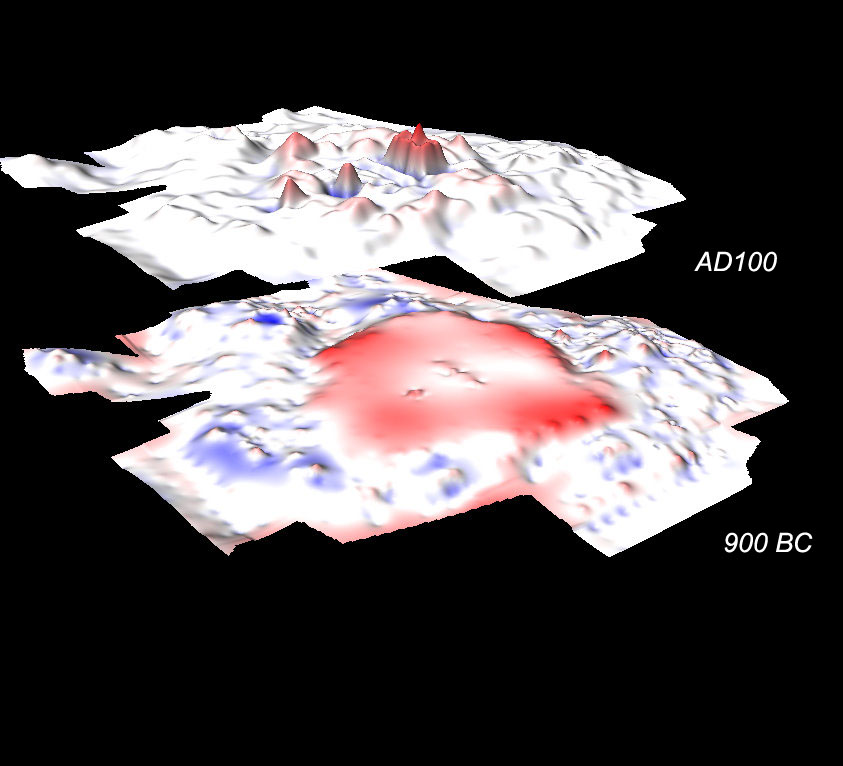

The first plaza was laid out on a modified hilltop overlooking the Holmul river ca. 900 B.C. According to excavation data, this was the largest construction project in the history of the site, involving the movement of an estimated 1.4 million cubic meters of fill onto the hill. One of the largest documented construction projects in Mesoamerica at that time. The plaza was the setting of the first architectural complex for public rituals. It was an E-Group (after the first excavated example, Group E of Uaxactun), with a long building on the east and a low platform on the west. According to our measurements, the building’s axis and corners lined up with the sunrise on the day of the zenith (May 10 and Aug. 3) and antizenith (Feb 1, Nov. 13). These dates are meaningful in terms of subdividing the solar year into quadrants and in marking the arrival of the rains in this part of the Lowlands.

According to archaeological dating, this complex and the foundation of the site date to the 9th century BC. Cival’s and the Mundo Perdido of Tikal are the earliest documented E-Group complexes in the Maya Lowlands.

Construction volumes at Cival compared

Cival’s ritual offerings

An elaborate offering was placed in this complex in connection with the foundation ritual. It included 20lb of jade. 103 pieces of polished blue-geen jade and five beautiful axes placed at the bottom of a pit. The shape of the pit, in plan view as in profile, is the Maya k’an cross sign, which in Maya cosmology represents the shape of the cosmos, the center and the four directions as well as an opening into the world of supernaturals. Above the jades were five water jars, representing rain deities pouring water onto sprouting ears of maize (the axes). In Maya religion, at the beginning of creation, five maize plants emerged from the earth and became the corner world trees that support the sky. The Cival cache is one of the earliest and best preserved cases of a long tradition of foundation offerings that reflect the cosmovision of the Maya and of many other Mesoamerican peoples. A similar jade axe cache was recovered by Willys Andrews at Seibal in the 1960s. Contemporary jade caches such as this have been found at the Olmec site of La Venta, Tabasco and other less known sites in Chiapas (e.g. San Isidro). Much later examples of the Mesoamerican tradition of cosmic jar-and-jade offerings can be found in the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan and the Aztec Temple Mayor at Tenochtitlan.

Cival cache 4, 800-900 BC

Architecture, sculpture and painting at Cival.

Over the one thousand years following the foundation, many temples and palaces were erected on the hilltop following the E-W alignment established by the E-Group complex. Overall four more E-Group plaza were built in the ceremonial zone around the main plaza and five large pyramidal complexes. These are located along the four extremes of the site’s center. The North Pyramid, the West Pyramid (or Structure 20), the South Pyramid and the Triadic Group 1, on the east. Of these, the eastern was the largest, supporting a triadic pyramid complex (Triadic Group 1). In its first version, its platform rose a mere 3.5 meters above the plaza. In its fifth enlarged version, its platform stood 20 meters above the plaza and supported three pyramids. The temple of the eastern pyramid rose an additional 13 meters above the platform. While much of the façade of the last remodeling was destroyed by millennia of jungle growth and erosion, the second-to-last version was preserved until looters disturbed it in the 1970s. The looters’ tunnel fortuitously stopped short of destroying a giant modeled stucco carving that adorned the pyramids front. During the 2003 excavations, the carving was completely uncovered and documented. It measures 5 meters from side to side and 3 meters top to bottom. It decorated the sloping side of the highest of the pyramid’s three terraces to the left (north) of a narrow central stairway. In 2004, a second matching sculpture was found on the other side of the stairway leading from the plaza to the upper temple.

These types of monumental carvings decorating the facades of Maya pyramids are referred as ‘masks’ in the specialized literature because they represent anthropomorphic or zoomorphic faces of deities. The sculpture was rendered in exquisite cream-colored stucco. Details of the eyes and mouth were painted in red and black. The deity portrayed here has eluded certain identification but it appears to combine elements of solar and rain deities and may be more directly related to a multi-faceted primordial god of the sky, known from the Colonial period Popol Vuh Maya-K’iche’ creation story as ‘hearth of sky’. Its iconographic motifs suggest that it represents the same supernatural as the masks of the lower terraces of the 5C-2nd pyramid of Cerros, Belize (dated to ca. 50 BC)[ii].

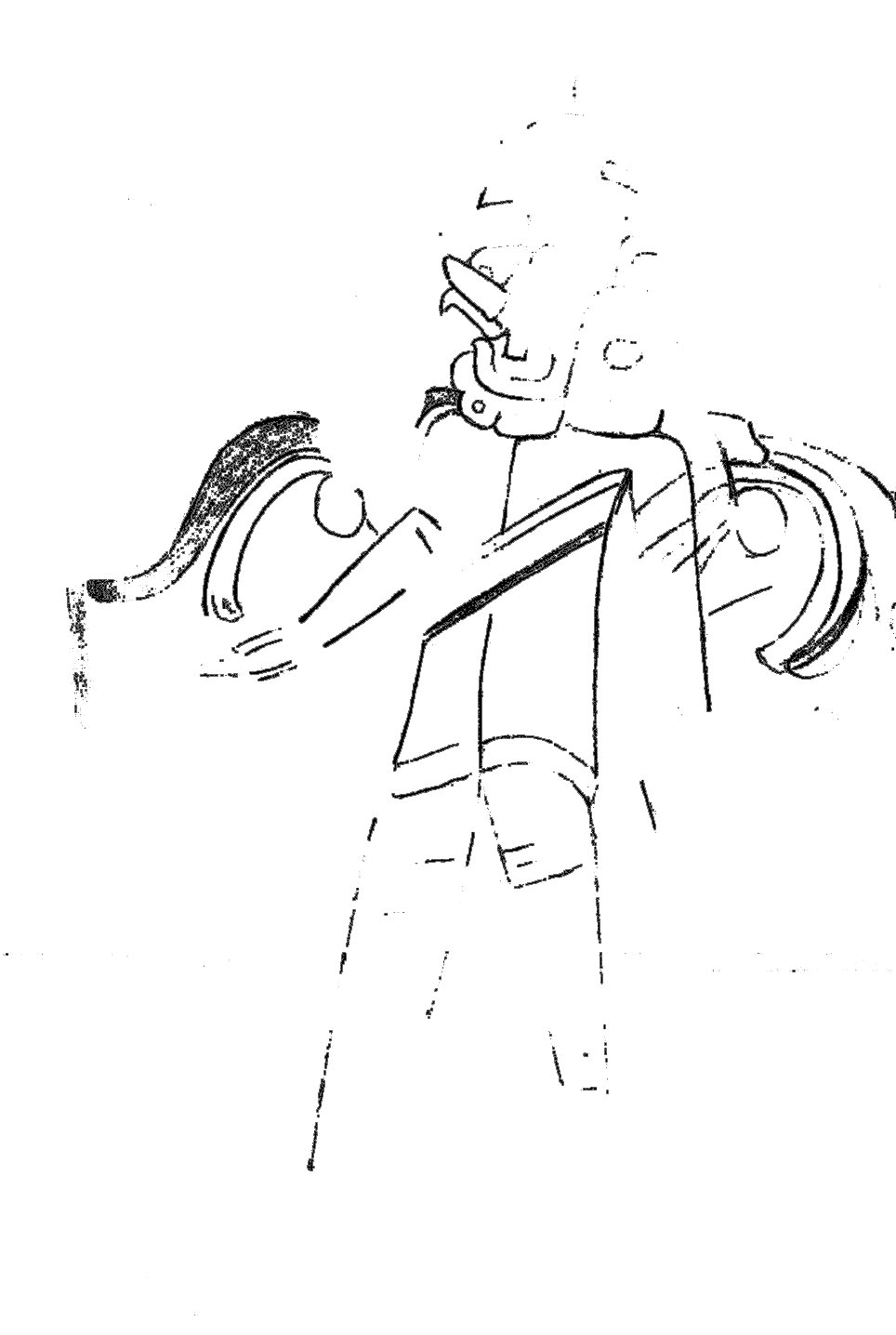

The temple that stood at the top of the eastern pyramid of the Triadic Group 1 has been largely destroyed by a massive looters’ trench, unfortunately. Only fragments of its interior walls survived. On a portion of wall in the temple’s rear room several (13) painted figures were found in 2005. These are painted relatively randomly on different areas of the wall. All appear to represent the human figure of the young maize god in a variety of dresses. In one example, he is wearing the trilobed royal crown (the hun jewel). In another, he is wearing the headdress of the Principal Bird Deity, also an emblem of royal power later worn by Maya kings. Two figures appear to be wearing a feathered cape. The ordering (or lack of order) of these figures and the painting style suggests that these images were painted at the end of ceremonies carried out in the temple room by different priest over time.

Cival mural 1, Figures 1, 2 and 13. Drawing by Heather Hurst

Radiocarbon samples taken from the masks’ stucco date the second-to-last version of the Triadic Group 1 pyramid to ca. 200 BC. Roughly at the same time as the masks were carved on the pyramid façade, a large stela was placed in the plaza below. On one side is the carving of a human figure in striding posture. The head is missing by a large bird-effigy pectoral can be seen on his chest. This is an emblem of royal power worn by Preclassic kings (see La Mojarra stela, and Principal Bird Deity headdress of painted figures described above). The style of the carving appears extremely early, 300-200 BC based on Nikolai Grube’s estimate and our reconstruction of its original setting in the plaza floors. So far, this is the earliest existing example of a Maya ruler image carved on a stone monument.

Cival Stela 2. Drawing by Nikolai Grube Stela 2 ( photo F. Estrada-Belli 2008)

Cival prospered for the next 300 years. Much of the population occupied the hills and ridges surrounding a very large ‘cival’ seasonal swamp to the north of the site and the Holmul River to the east. Farming was facilitated by the deep soils and the abundance of moisture throughout the year. Yearly floods also replenished the nutrients in the low-lying areas. Housing was organized in patio groups of 2-5 houses above a platform. Some were quite large and elaborate with high platforms and masonry buildings and were probably occupied by the elite segment of society.

Cival’s end

For reasons that are still largely unknown this all came to an end around AD 200. What we can say with any level of certainty is that the last major remodeling project in the ceremonial center, the enlargement and re-facing of the Triadic Group 1 occurred around than AD 100. In that same century, a long and poorly constructed wall was built around much of the ceremonial center on the hill. This was peculiar in lacking mortar and being made of cut stones taken from existing building. It also cuts across platform and even buildings. It appears to be more like a barricade than a permanent feature of the site. We interpret it as a last line of the defense for the Civaleños at a time, between AD 100 and 200 in which they were besieged by an unknown enemy. Following the construction of the wall, most of the buildings in the center and in the surrounding countryside were abandoned. Only a small sector of the population remained in selected areas of the site. We excavated on Group VIII a house that probably housed an elite family through the 4th century. The E-Group plaza also saw one last remodeling, but very limited in scope. From all this evidence we have to surmise that even this remnant elite group left the site shortly after AD 350. After this date, we have absolutely no evidence of occupation on the main hill, until the present. Our survey in the outer areas of the surrounding landscape found only sporadic occupation in the Late Classic and almost non for the Early Classic. For unknown reasons, the Cival center was shun away for the entire Classic period, even though centers like Holmul and Witzna’ had dense populations nearby.

In addition to the final war/siege, environmental causes such as drought of environmental degradation (soil loss) may have prevented a return of farming in the Cival area. However, the existing evidence from nearby lake deposits show no clear markers of climate change or environmental degradation until the end of the Classic period. Although an alteration of the lakes’ water depth may have occurred around AD 400 –too late to account for the end of Cival.

However, our ongoing analysis of environmental variables from these lake deposits is giving clear indications of marked drought episodes from AD 850 to 1050, in correspondence with the collapse of cities in this region of the Maya Lowlands.

Conservation at Cival

The site boasts impressive pyramids. At present, the Holmul Archaeological Project’s four caretakers maintain the main plazas free of undergrowth and patrol it daily. Part of their duties involve the upkeep of several thatch roofs that have been placed over exposed architecture (looters’ trench in Triadic Group 1) and over Stela 1. The also maintain the camp’s thatch structures and the trails to and from the site.

The first order of priority is the consolidation of the tunnel leading to the masks in Triadic Group 1 to allow visitors to see them. In addition, the rear side of the building is in need of further consolidation as the looters’ trench continues to erode part of this important structure.

Using a 3d laser scanner it is possible to accurately document the sculptures in minute detail. This can help longterm study and conservation efforts. It then be reproduced as 2d print-outs at 1:1 scale or viewed in 3d digitally on the web.

The consolidation of the tunnel and upper structure would ensure the permanent preservation of this important work of art and the ability of visitors to appreciate it in its original setting.

Funds are needed to finance the consolidation and scanning of the masks of Cival.

The Cival mask at the time of discovery Looters’ trench in rear of Cival masks, partly filled and roofed and 2008 field school students

As archaeological research continues at the site additional structures of great architectural significance might become known and eligible for conservation as cultural resources for tourism.

Cival and forest conservation

Cival is still in a heavily forested and natural conservation area designated by the Guatemalan goverment in 1990 as the Maya Biosphere Reserve. This area is the largest tract of tropical forest north of the Amazon and is refuge for many endangered species of fauna and flora.

Many rare hardwood trees are found within the site, cedar, mahogany and santa maria are among the best known. Sightings of jaguars, peccary, deer, crocodiles and the elusive tapir are common in the area. Our project’s caretakers maintain the main plaza and the largest buildings relatively free of undergrowth under the original tree canopy. Several trails lead through the extensive ceremonial area and surrounding landmarks, such as the Holmul river aguada (camp), the cival sinkhole, and the cival swamp (north) where a variety of rare birds can also be observed. Among them are, toucans, green parrots, owls, hawks, turkeys, and Curacao birds (pajuil or pheasant). Especially noticeable are the loud oropendulas.

In order to preserve Cival as a cultural and natural marvel, it is imperative that we continue to protect the site against illegal logging, poaching, deforestation, fires as well as illicit excavation of the Maya ruins. Local community-based logging concessions that operate in this area have been conserving the integrity of the site’s natural setting since the late 1990s as required by the terms of their concession. These concessions have been the only real barrier against forest fires, invasions and deforestation. However, they are constantly under threat by special interests that wish to subvert the current status of the Maya Biosphere Reserve . Presently, the Holmul Archaeological Project employs four park rangers on a year-round basis to protect these sites. However, funding is needed to guarantee the protection of this site in the future independently of the ups and downs of research budgets and of limited government resources.

Further Reading

Estrada-Belli, Francisco

2002 Anatomía de una ciudad Maya: Holmul. Resultados de Investigaciones arqueológicas en 2000 y 2001. Mexicon XXIV(5):107-112.

2005 Cival, La Sufricaya and Holmul: The long history of Maya political power and settlement in the Holmul region. In Archaeology in the Eastern Maya Lowlands: Papers of the The 2004 Belize Archaeology Symposium, edited by Awe, J., John Morris, and Shirley Jones pp. 193-208. Institute of Archaeology, Belmopan, Belize.

2006 Lightning Sky, Rain and the Maize God: The Ideology of Preclassic Maya Rulers at Cival, Peten, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 17(1):57-78.

2010 The First Maya Civilization. Ritual and Power in the Maya Lowlands before the Classic Period. Routledge, London/New York.

Estrada-Belli, Francisco (editor)

2001-2009 (editor) Investigaciones arqueológicas en la region de Holmul, Petén, Guatemala. Informes preliminares. Boston University. Available Online at http://www.bu.edu/holmul/reports

Estrada-Belli, Francisco, Jeremy Bauer, Molly Morgan and Angel Chavez

2003 Symbols of early Maya kingship at Cival, Petén, Guatemala. Antiquity 77(298).

Estrada-Belli, Francisco, Nikolai Grube, Marc Wolf, Kristen Gardella and Claudio Guerra-Librero

2003 Preclassic Maya monuments and temples at Cival, Petén, Guatemala. Antiquity 77(296).

Estrada-Belli, Francisco, Judith Valle, Chris Hewitson, Marc Wolf, Bauer Jeremy, Morgan Morgan, Carlos Perez, James Doyle, Edy Barrios, Angle Chavez and Nina Neivens

2004 Teledetección, patrón de asentamiento e historia en Holmul, Petén. In XVII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, edited by Laporte, J. P., B. Arroyo, H. Escobedo and H. E. Mejía, pp. 73-84. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala.

Schele, L. and Freidel, D. A., (1990) A Forest of Kings. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Sharer, Robert J. and Loa P. Traxler

2006 The Ancient Maya. 6th ed. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

[i] The Holmul Archaeological Project began with academic support by Boston University, then by Vanderbilt University (2001-2007), and presently by Tulane University. In addition, over the years the HAP has received support from many funding institutions: National Geographic Society, National Science Foundation, FAMSI, The Ahau Foundation, The Reinhart Foundation, The New World Foundation, Alphawood Foundation, and private companies: ARB-USA, Toyota Motors, Yamaha-Motors, PIAA lights, Interco Tires Co., Optima Batteries, Garmin, American Racing, Traimaster, Bushwacker, Borla, Rhino Linings, Leer, Procomp Tires, Warn Industries, Holley, Flowmaster, K&N, ITP, Eureka as well as many private individuals. The research has been possible thanks to government permits by the Ministry of Culture and Sports of Guatemala (IDAEH) and the work of many dedicated officials. Various scholars collaborated with their expertise to the research and conservation: Dr. Magaly Koch (Geology/Remote Sensing, BU), Dr. Gene Ware (multi-spectral imaging, BYU), Dr. Nikolai Grube (epigraphy, U. Bonn), Dr. David Wahl (paleo-environmental studies USGS-SF), Alberto Semeraro (mural conservation, Accademia di Carrara), and many young scholars whose PhD. Theses developed out of their work with HAP: Michael Callaghan (Preclassic ceramic production, PhD Vanderbilt U, 2008, Alex Tokovinine (ritual space and performance, PhD Harvard U, 2008), John Tomasic (Preclassic political economy PhD Vanderbilt U. 2009) and Heather Hurst (painting, PhD Yale U 2009). In addition, many graduate and undergraduate students contributed their work every year.

[ii] Schele and Freidel 1990